CHAPTER 1 - What are human rights?

Human rights are entitlements and freedoms of all human beings, whatever our nationality, place of residence, sex, age, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, language, or any other status. Human rights are held by all persons equally and universally. They are based on core principles like dignity, fairness, equality, respect and autonomy. Human rights are present in our day-to-day lives and protect our freedom to control the different aspects of our own lives.

1.1 How are human rights guaranteed?

Human rights are expressed and guaranteed by law, such as international treaties and national constitutions and/or laws. The first global expression of human rights being entitled inherently to all human beings was achieved after World War II. The foundational text that reflects this global consensus is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) that was adopted by the United Nations in 1948. After the adoption of the Universal Declaration countries have adopted many human rights treaties that lay down obligations of governments to act in certain ways or to refrain from certain acts, in order to promote and protect human rights and fundamental freedoms of their citizens. These treaties constitute what we call international human rights law or framework. Accepting the provisions of such treaties creates legal duties on States to ensure everyone in the country can enjoy these rights and to provide remedies if they are violated. International human rights law lays down obligations of governments to act in certain ways or to refrain from certain acts, in order to promote and protect human rights and fundamental freedoms of individuals or groups. It makes governments accountable to the international community and foresees specific measures and sanctions that can be taken against the state that does not fulfil these obligations. This handbook explains how older people can advocate under international law and is not concerned with how they can claim their rights at the national level. It can be very useful in order to put pressure on governments to comply with their international obligations.

Universal human rights

To understand the history and concept of universal human rights you may watch this video.

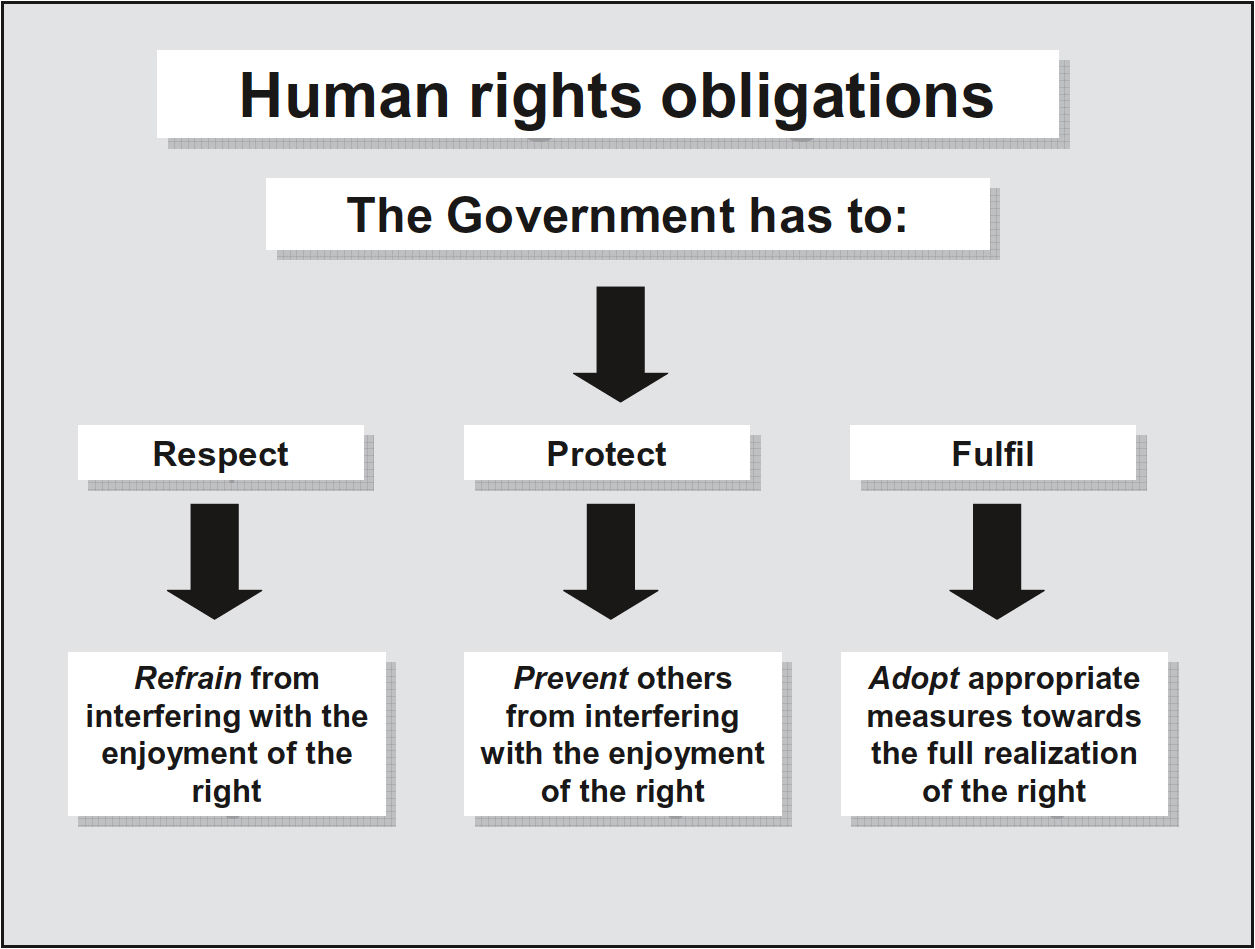

1.2 What are state obligations under international human rights law?

When states agree to international treaties (through a process called ratification), they assume the obligations to respect to protect and to fulfil the human rights that are included in these treaties. The obligation to respect means that States must refrain from interfering with or limiting the enjoyment of human rights. It is also described as a negative obligation, as the state has to abstain from violating human rights. The other two obligations include positive duties, which means that the state has to take action to deliver rights. The obligation to protect requires States to interfere in order to protect individuals and groups against human rights abuses by others, in particular private, actors. obligation to fulfil means that States must take positive measures to facilitate the enjoyment of human rights.

To illustrate the type of measures that action must take to ensure that citizens can enjoy their human rights, we will use the examples of the rights to work and to health2.

Image from OHCHR, Factsheet 33, Frequently Asked Questions on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

The right to work

In the context of work rights, the obligation to respect means that the state must not use forced labour or deny political opponents work opportunities. It also means that the state should not discriminate against specific groups of people, like migrants, religious minorities or older workers when it selects civil servants. The responsibility to protect means that the state must ensure that employers, both in the public and in the private sectors, pay the minimum wage. It should moreover ensure that employers do not apply age limits in their recruitment policies. To do so, the state may need to carry out inspections or pass legislation regulating minimum wage schemes and equality policies. Under its responsibility to fulfil the State must provide opportunities for the enjoyment of the right to work for example by, offering training for groups at risk of long-term unemployment, a risk faced notably by older workers made redundant.

The right to health

To comply with its obligation to respect the right to health, the State must not deny access to public health facilities on a discriminatory basis, for example to the Roma population. In addition, the obligation to protect means that the State must control the quality of medicines marketed in the country by either public or private suppliers. Its duty to fulfil includes the facilitation of the enjoyment of the right to health, for example, by establishing flu vaccination campaigns for older people. It also entails promoting the right to health through awareness raising campaigns, for example on the correct use of antibiotics, a key issue for older people who need for example hip surgery or heart surgery and are confronted with the risk of increasing antibiotics resistance.

These two examples showcase that the duty to fulfil is quite far-reaching: it includes an obligation to facilitate access to goods and services that are necessary for the enjoyment of a right (for example through occupational training, or through regulating the market so that consumers have access to essential goods and services, such as medication, food and electricity), to promote through providing information to citizens so that they can make informed choices (for example, information campaigns about the detrimental effects of smoking or the importance of physical activity for active and healthy ageing) and to provide some essential goods and services (for example access to water, housing for vulnerable groups, shelters for victims of abuse, etc)3.

The latter obligation to provide does not mean that the State should provide all goods and services for free. It means however that essential services like housing, food, water, sanitation, health or education should be available at affordable prices in order not to prevent a person from accessing these services and not to compromise his or her ability to enjoy other rights (as for instance lack of housing may jeopardise a person's ability to enjoy his or her rights to water, sanitation and private and family life). Of course in some instances, ensuring equal enjoyment of rights may involve providing subsidized or free services to those who would otherwise not be able to enjoy certain rights, for example for the poor, unemployed and most vulnerable.

What are the State obligations in cases of elder abuse?

Imagine the following three cases of elder abuse:

- An older person is sexually abused in a public nursing home.

- An older person is physically abused by his/her caregiver, who is recruited by the municipality to deliver care services at home.

- An older person is a victim of financial abuse by his/her daughter with whom he/she lives.

From these examples, only in the first case the abuse takes place in a public institution (i.e. nursing home). In the other two examples the human rights violation occurs in the private home of the older person. Whereas in the first case there is an obvious direct obligation of the state, as the public nursing home is funded and operated by the state, it does not mean that the state is free from responsibilities in the other two cases. Let's see what the state could do to prevent and remedy the abuse in those cases.

First, as we have explained above, the duty to protect includes the obligation of the state to intervene in private relationships in order to prevent violations by other actors, like professionals, businesses or individuals. At the same time this does not mean that the state can possibly prevent all cases of abuse; it however has an obligation to make reasonable efforts to avoid such situations and in case they occur, to offer redress and support to the victim. But what does "reasonable efforts" mean?

Obviously the state cannot put a policeman or install cameras in everyone's home, to make sure that people are safe. This is not only impossible due to the important financial and human resources that such a measure would implicate, but also because such a policy might interfere with the right to privacy. The state can however take other types of action to prevent cases of elder abuse.

For example, the state can provide or facilitate training to caregivers so that they improve the quality of care provided and avoid abusing older people. It can moreover undertake inspections and regularly monitor how care at home is provided in order to promptly identify if some things in the care delivery should be changed. It could moreover provide respite care or other forms of support for informal caregivers so that they avoid exhaustion, which can lead to abuse. It may also raise public awareness of the risk factors and prevalence of elder abuse. In addition, when a case of abuse is reported the state should initiate an investigation to identify the perpetrator and also provide legal and social assistance to the victim. The state might also have to amend its law so that abuse of older people can be prosecuted in a similar way to domestic violence against women. In addition, the state should ensure the proper and impartial functioning of its judicial system, so that the case is dealt within a reasonable timeframe.

In other words the state does not have an obligation to prevent all cases of abuses, which would be impossible. It has however a duty to take necessary means to attempt to avoid such situations, including in private and inter-personal relations. This is particularly important because an increasing number of organisations (such as voluntary or for-profit companies), are providing basic goods and services, which are related to the realization of the human rights of older persons (like health and long-term care). In such cases, the State still carries the obligation to ensure that such organizations and enterprises respect human rights norms and standards in the delivery of these goods and services. It has to take all measures that would be reasonable expected to deter human rights violations.

For example, in a recent case (McDonald v UK), the European Court of Human Rights considered for the first time that States have positive obligations to ensure that the provision support to an older disabled person respects the right to private and family life. Moreover it held that social care services need to respect human dignity, otherwise there might be a violation of this right.

In this judgement the Court considered whether there was a breach of Ms McDonald's rights when due to the reduction of her care package she was asked to use absorbent sheets and sanitary pants, instead of allocating an assistant that would help her use the toilet. The Court found that the UK had not fulfilled its obligations as it failed to draft a proper care plan for Ms McDonald before reducing the amount allocated for her care, as this was something that was reasonably expected by the state and would avoid an interference with her right to respect for her family and private life. However, for the period after the state revised Ms McDonald's care plan, the Court found no breach due to the reduction of the care package because the State had considerable discretion when it came to decisions concerning the allocation of scarce resources.

Overall, although the Court in the end ruled that Member States have a wide margin of appreciation regarding how to deliver care and that it's up to national authorities to make a proper balance between care needs and available resources, the decision established that 'a failure to consider a person's dignity can be a breach of human rights' 4. This may be a basis upon which to claim future cases around care and elder abuse.

1.3 Who provides for human rights at international level?

Besides the United Nations, other international organisations, including the Council of Europe and the European Union have elaborated human rights documents and established bodies and processes to monitor their implementation by national governments. One of the most important instruments in the European context is the European Court of Human Rights that rules on the application of the European Convention on Human Rights by the States that have accepted its provisions. Other international bodies exist that also protect and promote human rights, for example the African Union and the Organization of American States. However, for this text we will focus mainly on the UN, the EU and the Council of Europe as they are most relevant for older people living in Europe..

THE UNITED NATIONS

In 1945, after the Second World War ended, 51 countries founded the United Nations (UN), formerly known as the League of Nations, for the ultimate maintenance of peace. Today, the UN has 193 members that express their views through special UN bodies like, amongst others, the General Assembly (GA), the Security Council and the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). Its founding Charter lays down the basic and fundamental principles of the United Nations. The UN General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in 1948. The declaration constitutes rights of the individual such as the right to life, prohibition of slavery, freedom of movement, freedom of association, thought, conscience and religion. It also sets out social, economic and cultural rights, such as the right to work and social protection.

Although the UDHR does not have a legally enforcing power, both states that have signed it but also those who have not, have committed to its tenets and should consistently align their laws, policies and conduct with the principles of the declaration in good faith. Any government that violates the UDHR, does so at the risk of domestic and international outcry.

You may watch the following video explaining the history of the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the UN, and the important role that Eleanor Roosevelt, the wife of the late U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, played in that process.

The Universal Declaration was followed by a series of international treaties (variously named Covenants or Conventions) focusing on specific categories of rights (civil and political, economic, social and cultural) or specific groups (women, children, migrant workers, persons with disabilities) or wrongful activities (genocide, torture, racism). These treaties are binding for those countries that have ratified them and flesh out the rights that human beings can claim and for which governments have specific obligations, as outlined in the previous section 1.2. They have elaborated on the UDHR and manifest the principles of equality, dignity and respect, which is why - despite this variety of instruments - human rights are considered universal, inalienable, indivisible and interdependent.

What is the force of human rights conventions?

When a human rights convention is signed and ratified by a state, the state must submit reports highlighting how its laws and practices are following the rights set out within the convention. Most conventions set up bodies (called committees or treaty bodies) that oversee the implementation of the legal document, which in some cases hold little power but in other cases have strong political and legal authority. Some examples of UN conventions are the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination, the Convention Against Torture, the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Meeting at the UN Human Rights Council, Geneva, Switzerland

As the UN deals with both human rights and other international matters such as developing friendly relations among nations and helping nations work together to improve the lives of poor people, there are separate sub entities and groups within the UN that focus solely on human rights. The main human rights body of the UN is the Human Rights Council (HRC), which is made up of 47 states (elected periodically by the General Assembly) that acts as an inter-governmental committee that is responsible for the promotion and protection of all human rights on a global scale. The High Commissioner for Human Rights is the principle human rights official of the United Nations. The High Commissioner is assisted by a secretariat called Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

The mandate of the OHCHR is to provide assistance to governments to help implement human rights standards - enshrined in UN documents - on the ground. It also works with civil society, national human rights institutions and other UN entities and international organisations, such as the International Labour Organisation (ILO), the International Criminal Court, the World Bank and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) to promote human rights. The office also supports the work of treaty bodies that monitor states' compliance with core international human rights treaties and the Special Procedures of the Human Rights Council, which include independent human rights experts - also known as special rapporteurs - with mandates to evaluate the protection of human rights from a thematic or country-specific perspective.

How does the OHCHR work?

The office’s main structure of work is made up of three major dimensions:

- Standard setting: providing a solid basis of work for other organisations to see and follow

- Monitoring: evaluating states’ compliance with UN human rights instruments and investigating how states are protecting human rights

- Implementation on the ground: examining to what extent societies, communities and individual persons are having their rights protected and promoted by the state

The Civil society unit of the OHCHR provides information and advice to civil society organisations on a broad range of human rights issues and assists civil society in engaging with the United Nations human rights bodies and mechanisms. NGOs can contact the office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights via email: civilsociety@ohchr.org

For more information on the United Nations framework on the rights of older people see chapter 2.

THE COUNCIL OF EUROPE

The Council of Europe (CoE) promotes cooperation between European countries in the areas of human rights, democracy and the rule of law. Founded in 1949, the Council of Europe now has 47 member states. The Council of Europe’s headquarters are in Strasbourg, France.

What is the difference between the CoE and the EU?

The Council of Europe should not be confused with the European Union (EU) and in particular the European Council, which is an EU institution consisting of the heads of state or government of the 28 EU Member States. The Council of Europe is an independent inter-governmental organisation, although all EU Member States are also members of the Council of Europe. No country has ever joined the European Union without first having been a member of the Council of Europe. To better distinguish the Council of Europe with EU and other international organs you may have a look here.

The European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, France

All Council of Europe member states have signed up to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) - based in Strasbourg - supervises the enforcement of the European Convention on Human Rights at the national level. Individuals can bring complaints of human rights violations to the Strasbourg Court once all possibilities of appeal have been exhausted in the member state concerned.

The Council of Europe also promotes human rights through thematic international conventions, such as the Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence and the Convention on Cybercrime. It monitors member states' progress in these areas and makes recommendations through independent expert monitoring bodies.

The current Commissioner for Human Rights of the CoE,

Nils Muižnieks

The European Social Charter is another Council of Europe treaty, which guarantees social and economic human rights. It was adopted in 1961 and revised in 1996. The European Committee of Social Rights examines the conformity of States with the European Social Charter.

The Commissioner for Human Rights is an independent mechanism within the Council of Europe mandated to promote awareness of and respect for human rights. The Commissioner can make country visits and write reports in order to encourage policy reforms and improve the protection of human rights on the ground.

You may watch the following video introducing the Council of Europe and its bodies as well as a speech by its current Secretary General, Mr. Thorbjørn Jagland, explaining the role of the Council of Europe in promoting and protecting human rights..

For more information on the Council of Europe framework see chapter 3.

THE EUROPEAN UNION

Mr. Stavros Lambrinidis, Fist EU Special Representative for Human Rights

The European Union (EU) is bound by its founding treaties, according to which respect for human rights counts among the Union’s fundamental values. The Treaty of Lisbon, adopted in 2009 introduced a new focus on human rights enshrining the binding force of the Charter of Fundamental Rights. The EU has also established the Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) as a consultative body of the EU institutions and has also appointed a Special Representative for Human rights (EUSR) whose role is to enhance the effectiveness and visibility of EU human rights policy outside its borders. The human rights of European citizens are also protected by specific laws and policies of the European Union, such as equality directives, strategies and guidelines. According to the Treaty of Lisbon the EU is supposed to accede to the European Convention on Human Rights. When this happens, the EU will fall under the scrutiny of the European Court of Human Rights. There are currently discussions between the EU and the Council of Europe in order to make this happen.

You may watch the following video by the European Parliament describing EU’s current human rights challenges.

For more information on the European Union framework see chapter 4.

1.4 How are human rights enforced at national level?

While international human rights treaties can help raise awareness of human rights and improve the situation of people on the ground through domestic implementation, ultimately their impact will depend on how they are effectively enforced by State parties. The following chapters 2, 3 and 4 explain the different ways that States’ compliance is monitored and what civil society can do in case their country does not conform with its obligations under international human rights law.

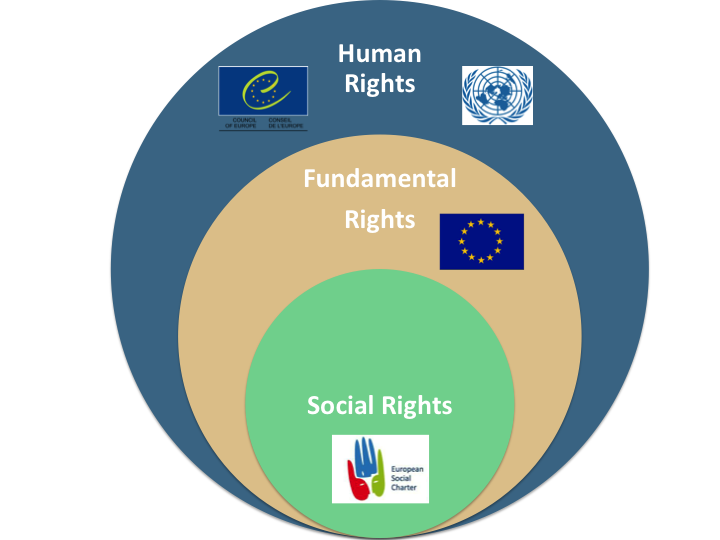

1.5 Is there a difference between human rights, fundamental rights and social rights?

Often there is confusion as to what the terms ‘human’, ‘fundamental’ and ‘social’ rights mean. Depending on the context and whether we refer to the national or international level, people may have diverging understandings of these concepts. Here we will try to debunk the myth around these notions and explain how they should be understood when advocating the rights of older people within European and international bodies.

As explained above, 'human rights' is the general term used to refer to the individual entitlement of all human beings to live in dignity and enjoy freedom and autonomy. This is the word most commonly used by the United Nations and the Council of Europe when they take action to promote and protect the rights of citizens. The European Union however has adopted the term 'fundamental rights', which relates to the Union’s Charter consolidating the rights that it should respect across all its actions. In other words, under international human rights law there is no one right that is more fundamental than another; the difference in terminology depends on the legal order and the legal framework to which we refer.

Another concept widely used is that of 'social rights'; this is particularly important for the subject of this handbook, as many of older people’s rights fall under the category of social rights, which include issues around welfare, employment and pensions. National legislation on social protection and health care fall under the remit of a state’s social provisions, which explains why this term is widely used in the ageing sector. Social rights, such as labour, pension or housing rights, are human rights and should be equally respected and promoted by governments. However, at the same time governments should cater for what we call civil and political rights, which, among others, include older people’s access to justice, freedom of expression, protection from abuse and political participation. So, ‘social rights’ cover only a part of older people’s lives.

Social Rights in conventions of the International Labour Organisation (ILO)

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) is a specialized UN agency based in Geneva, bringing together representatives of workers, employers and governments. ILO has adopted a number of conventions promoting rights at work, decent employment opportunities and social protection, amongst other issues. These conventions are the result of international tripartite social dialogue between governments, labour and employers’ organisations. Although they do not formally constitute human rights treaties, ILO conventions establish how work-related social rights can be put into effect. This is why it is useful to take them into account to understand how social rights can be applied in practice. For example the ILO adopted in 1967 Convention no.128 concerning Invalidity, Old-Age and Survivors’ Benefits and in 2012 Recommendation No.202 National Floors for Social Protection.

In other words, ILO provides with technical expertise and labour standards and guides policy change in compliance with the human rights framework enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

Philip Alston, UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, in 2014 urged governments around the world to embrace the United Nations Social Protection Floor Initiative to ensure guaranteed basic income security and access to essential social services for all.

He stressed: “The use of human rights language does matter. Let me apply this to the plight of those living in extreme poverty. Recognition of their human rights acknowledges their dignity and agency, empowers them and their advocates, and provides a starting point for a meaningful debate over the allocation of societal resources. We need to acknowledge the extent to which governments and the international community are intentionally avoiding the language of human rights in the context of development debates, and to ask ourselves why this is happening. Perhaps it is precisely in order to avoid all of the positive consequences of using human rights language”.

In reality, the enjoyment of all human rights is interlinked. For example, it is often harder for individuals who do not have access to adequate resources, to take part in political activity or to exercise their freedom of expression. This is why in practice it makes little sense to distinguish between “civil and political rights” and “economic, social and cultural rights”, which is the wider family of social rights as it is described in international law.

At national level - depending on the country in question - either the term ‘human rights’ or ‘fundamental rights’ may prevail or national laws and constitutions may use both interchangeably or rather refer to one category, such as ‘social rights’. These differences should not pose a problem in our understanding of how governments should conform to their international obligations, since – as shown above – they all emerge from the common principles and values of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Nevertheless, traditionally countries have understood social rights differently than civil and political rights. The reason for this conceptual distinction is that social rights are believed to require positive action and high levels of investment, while civil and political rights are said simply to require the State to refrain from interfering with individual freedoms. While this is in general true, social rights also require the state not to interfere with individual freedoms, for instance trade union freedoms or the right to seek work of one’s choosing. Similarly, civil and political rights, also require investment for their full realization. For example, civil and political rights require infrastructures such as a functioning court system, prisons respecting minimum living conditions for prisoners, legal aid, free and fair elections, and so on5.

What has been outlined above is also depicted in the image below; in sum, what one should remember is that all rights are of equal value and importance, regardless of the terminology used to describe them. For the sake of clarity this handbook adopts the simple distinction, by referring to ‘fundamental rights’ only when discussing the EU framework and the Charter of Fundamental rights, whereas in all other cases it uses the term ‘human rights’ or more simply ‘rights’.

Economic, social and cultural rights and progressive realisation

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, one of the main UN human rights treaties, as it will be explained in the next chapter, states in article 2 that states must 'take steps, individually and through international assistance and co-operation, especially economic and technical, to the maximum of its available resources, with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of the rights recognized in the ... Covenant by all appropriate means, including particularly the adoption of legislative measures'.

This provision is only included in this treaty and does not concern civil and political rights, which as we have seen imply primarily (although not entirely) negative obligations for states not to intervene with individual rights and freedoms. This specific condition was added for economic, social and cultural rights, because historically they were seen as having a different nature and entail more positive action by states.

What this means is that the Covenant admits that it is not possible to realise all human rights at once. Nevertheless that does not mean that states can use this as an excuse not to act at all. On the contrary, while the full realization of the relevant rights may be achieved gradually, steps towards that goal must be taken within a reasonably short time. Such steps should be deliberate, concrete and targeted as clearly as possible towards meeting the obligations recognized in the Covenant6. Governments must also demonstrate that they are using the maximum of available resources to continue improving the conditions of their citizens. They must also ensure that they are not discriminating, for example by offering free housing facilities to migrants but not to the Roma population. This obligation not to discriminate has an immediate effect. This means that even if states take several years to achieve their human rights targets, they are not allowed to discriminate against some parts of the population in order to attain progress in an area. In other words, governments should not for example – in the context of austerity – apply budgetary cuts that have as a consequence to exclude only non-nationals from access to health, or disproportionately affect only one part of the population, like older people.

For a case study on how older people can use this Covenant to challenge austerity measures, see the second chapter.

What did we learn in the first chapter?

- Human rights describe basic ways that all people in the world should be treated and recognise that every human has an equal value.

- Rights are listed in different legal documents, such as national constitutions and/or international conventions.

- They include every aspect of people’s lives, such as the right to work, to have a family, to go to school and to receive a pension.

- International human rights law imposes on states both positive (duty to take measures) and negative (duty not to interfere with individual rights) obligations to put these rights in effect.

- The United Nations is one of the organisations that is particularly active in promoting human rights. It has written down the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a document that aims to protect the human rights of everyone. The United Nations has also explained what countries should do to respect the human rights of vulnerable groups, such as children and people with disabilities.

- The Council of Europe has drafted the European Convention on Human Rights and has established a specific tribunal, called the European Court of Human Rights to decide how far countries are applying correctly the Convention.

- The European Union also aims to protect the rights of its citizens and fundamental rights are among the shared values of the EU Member States, which is why they are included in the documents that founded the Union.

- All rights - regardless of whether they refer to aspects of welfare or individual freedoms and the resources required for their implementation – are of equal value and importance.