CHAPTER 3 - How does the CoE provide for older people’s rights?

Although the Council of Europe has wide competences in the field of human rights, in most cases it creates ‘soft law’. This means that member countries do not face sanctions if they fail to comply with the guidelines, recommendations and principles outlined in these documents. In addition to soft law however, the Council of Europe produces binding treaties, such as the European Convention on Human Rights and the European Social Charter. These instruments are known as ‘hard law’ because they give signatories legally binding responsibilities to provide for individuals’ rights. This chapter of the handbook discusses the role of the Council of Europe (CoE) in promoting and protecting the rights of older people through soft and hard instruments.

3.1 What is the Council of Europe?

The Council of Europe (CoE) is an independent intergovernmental organisation founded in 1949 and headquartered in Strasbourg, France. The idea for the creation of a European organisation is often attributed to Winston Churchill who said referring to the United Nations, ‘[u]nder and within that world concept, we must re-create the European family in a regional structure called, it may be, the United States of Europe. The first step is to form a Council of Europe’ 1.

The Council of Europe was established after the Second World War ‘in order to achieve a greater unity between its members for the purpose of safeguarding and realising the ideals and principles which are their common heritage and facilitating their economic and social progress’ (Article 1a of its Statute). Since its conception, the CoE has sought to represent a Europe of peace, based on the protection of three central values: human rights, democracy and the rule of law. The CoE currently has 47 member countries which together represent 800 million people. The membership of the CoE includes all 28 Member States of the European Union; no country has ever joined the European Union without first being a member of the Council of Europe.

As an introduction, you can watch this video presenting briefly the inner-workings of the Council of Europe and its work on democracy, human rights and the rule of law.

Map of the 47 Member States of the Council of Europe

The role of national governments

National governments are directly involved with the Council of Europe in three distinct ways. The first is institutional: member countries and their elected representatives are democratically involved in decision-making processes in the CoE’s Committee of Ministers, Parliamentary Assembly and Congress of Local and Regional Authorities (more information about these organs can be found in following sections).

The second role played by national governments is constitutional: they must sign and

The third element of national governments’ involvement with Council of Europe actions concerns the implementation of treaties and soft instruments, which must be carried out within each country. Due to the specificities of different legal arrangements and views, implementation can take different forms depending on the country – but choosing between the many options is left to national governments.

To find out which Council of Europe treaties have been signed and ratified by your government, and thus what rules they are bound by, you can use this helpful tool, which has been provided by the Fundamental Rights Agency, and is specific to EU countries. To better understand how the European Social Charter applies in your country, please refer to Case Study 11.

Institutional structure of the Council of Europe

Please refer to following sections for more detailed information about these instruments, what they do and how they are relevant for you.

Secretary General and Deputy Secretary General

The Secretary General is elected by the Parliamentary Assembly for a five-year term (renewable once) to lead and represent the organisation. They are responsible for the strategic planning and direction of the CoE’s work programme and budget. A Deputy Secretary General is also separately elected to serve a five-year term.

Committee of Ministers

The Committee of Ministers is the CoE’s main decision-making body and is made up of the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of each Council of Europe member country and their Deputies.

Parliamentary Assembly (PACE)

The Parliamentary Assembly consists of 324 Members of Parliament (MPs) from all 47 national governments (note: these are members of national parliaments, not independently elected MPs of the CoE). PACE can investigate, recommend and advise national governments.

Congress of Local and Regional Authorities

The Congress of Local and Regional Authorities consists of 648 nationally elected representatives from more than 200,000 local and regional authorities operating on a national level which monitors CoE member countries. Like the Parliamentary Assembly, these are elected members of national level regional authorities.

Commissioner for Human Rights

A Human Rights Commissioner is elected every six years (not renewable) by the Parliamentary Assembly to independently promote awareness of and respect for human rights.

European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR)

The ECtHR is the permanent judicial body which guarantees for all Europeans living in CoE member countries the rights safeguarded by the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

European Committee of Social Rights (ECSR)

The ECSR monitors compliance with the European Social Charter (ESC). The Charter is considered to be the ‘other half’ of the European Convention of Human Rights and plays the role of a ‘Social Constitution of Europe’.

Conference of International Non-Governmental Organisations (CINGO)

The CINGO consists of between 300 and 400 international NGOs. It provides vital links between politicians and the public and brings the voice of civil society to the CoE.

The Council of Europe and the European Union

Both the Council of Europe and the European Union reflect the ideal coined by Count Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi between the wars: ‘A divided Europe leads to war, oppression and hardship; a united Europe leads to peace and prosperity’. Nevertheless, take care not to confuse the two organisations, in particular the Council of Europe with the European Council, which is an EU institution consisting of the Heads of State or Government.

Although the Council of Europe and some EU institutions have similar names and share the European flag for their logo, they are different organisations. Whereas the European Union is a political and economic union, the Council of Europe does not have as wide competences, but works to promote peace and human rights. For more information on how to distinguish the Council of Europe from EU and other institutions please follow this link or watch this clip.

Nevertheless, the European Union has a special relationship with the Council of Europe. It is permitted to sign selected CoE Treaties and agreements, and its legal system is very closely tied to that of the CoE. For example, the EU is preparing to sign the CoE’s European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), which once completed will result in EU actions being under the control of the CoE’s European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). This will allow the same level of human rights protection regardless of whether an action is a result of national or EU law. Official negotiations for the EU’s accession to the ECHR were launched in 2010 and remain ongoing. For more information about this see the section on EU’s accession to the ECHR.

Besides, the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights is largely based on the CoE’s European Convention on Human Rights and the European Social Charter, although the relationship also works in the other direction. For example, the revision of the European Social Charter drew upon, or made express reference to, EU Directives on the subject of labour law, such as the European Community Directive 91/533 on an employer’s obligation to inform employees of the conditions applicable to the contract or employment relationship (for more information about the European Social Charter please refer to following section). More information about the many similarities between EU law and the European Social Charter can be found in this Working Document, produced by the European Committee of Social Rights. Additionally, the Court of Justice of the EU often refers to case law of the CoE’s European Court of Human Rights, and vice-versa. Referring to each other’s case law is a clear example of how the two legal systems work closely together.

The EU and the Council of Europe also work together in other political and strategic ways to promote and protect human rights, democracy and the rule of law around the world. They take part in regular high-level consultations and the European Commission participates in some CoE activities. In addition to this, every two years the EU adopts Priorities for Cooperation with the Council of Europe.

In the most recently published of the EU’s Priorities for Cooperation with the Council of Europe, the EU lays out its collaborative plans for 2016 and 2017. Although older people aren’t specifically mentioned, these priorities include action to combat discrimination, i.e.:

- Fight against discrimination, promote and protect the human rights of persons belonging to minorities and vulnerable groups.”

- “Promote awareness of the CoE European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) activities and the implementation of its recommendations on all forms of anti-discrimination.”

- “Promote civil participation in decision-making and effective interaction of an active civil society with authorities.”

The CoE also collaborates with the EU’s European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), in the frame of the joint Collaborative Platform on Social and Economic Rights, which brings together the two organisations, the ‘European Network of National Human Rights Institutions’ (ENNHRI) and the ‘European Network of Equality Bodies’ (Equinet). The initiative aims to further economic and social rights in Europe by sharing information and increasingly working together. The first Platform meetings focused on (i) the CoE’s European Social Charter and how it could be better implemented to ensure its greater use in the context of economic austerity, (ii) the role of national equality bodies as watchdogs of social and economic rights on a national level, and (iii) integrating social rights in the EU’s Pillar of Social Rights and using indicators to monitor the effective enjoyment and respect of social rights and support Member States in this process.

In addition, since 1992, the EU and the Council of Europe have together implemented over 180 joint projects both inside the European Union and in wider Europe. For example, one such programme is ongoing in Bosnia and Herzegovina: the Prison Reform Programme. One action is to develop treatment programmes for vulnerable categories of prisoners, such as those who are elderly, physically challenged or disabled. This is in line with one of the main objectives of the project: to strengthen the professional capacity of prisons in Bosnia and Herzegovina in order to provide suitable support for people with specialist needs.

3.2 European Convention on Human Rights

The Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, most commonly known as ‘European Convention on Human Rights‘ (ECHR), is one of the most important human rights treaties. It was established to prevent a reoccurrence of the atrocities committed during World War II, and to safeguard Europe from the perceived threat of post-war communism. The original text of the Convention was drafted in 1950 and has been amended several times through fifteen additional Protocols– some dealing with the content of the Convention, others with procedural aspects of its monitoring and implementation. Protocols are binding only on those States that have signed and ratified them; when a State has signed a protocol but not ratified it, it is not bound by its provisions. Although all 47 Member States of the CoE are bound by the original text of the Convention, not all countries have ratified the additional Protocols. As a result, not all complementary protections and procedures apply to every country.

How can I learn more about the rights included in the Convention?

The text of the European Convention on Human Rights is available in all CoE languages here. To view all of the Protocols, you can refer to the full list of texts related to the ECHR. You may also watch this video for a brief overview of the rights enshrined in this key document or read the simplified version.

The Convention (and its additional protocols) 2:

Protects the rights to:

- life, freedom and security

- respect for private and family life

- freedom of expression

- freedom of thought, conscience and religion

- vote in and stand for election

- a fair trial in civil and criminal matters

- property and peaceful enjoyment of possessions.

Prohibits:

- the death penalty

- torture or inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment

- slavery and forced labour

- arbitrary and unlawful detention

- discrimination in the enjoyment of the rights and freedoms secured by the Convention

- deportation of a state’s own nationals or denying them entry and of the collective deportation of foreigners.

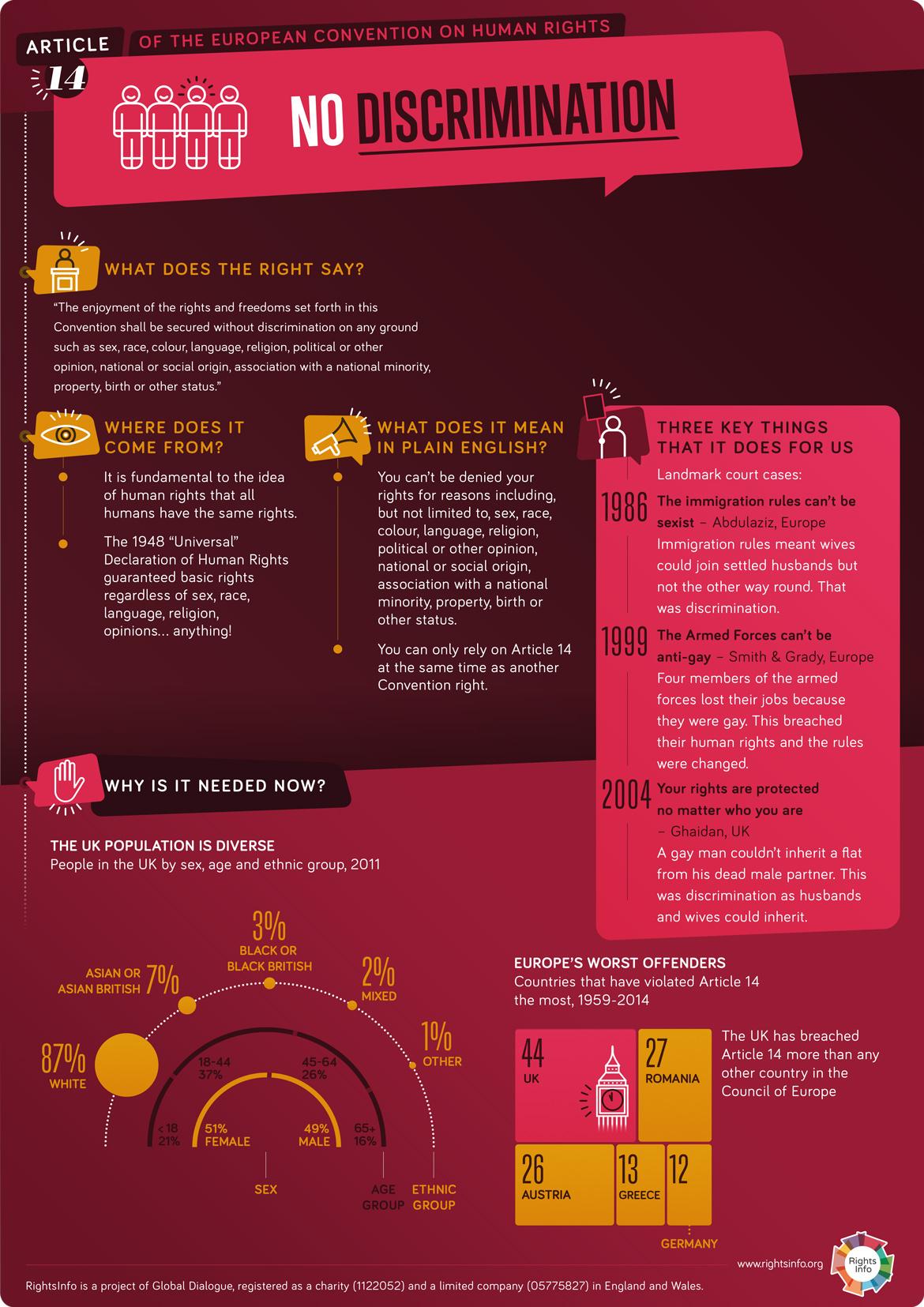

Age discrimination under the ECHR

All individuals should have access to the rights and freedoms enshrined in the Convention ‘without discrimination on any ground such as sex, race, colour, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, association with a national minority, property, birth or other status’. (Article 14 of the ECHR). This provision has limited effect because it only prohibits discrimination in the enjoyment of one of the other rights guaranteed by the Convention. Protocol No 12 removes this limitation and guarantees that no-one shall be discriminated against by any public authority. This Protocol states that “The enjoyment of any right set forth by law shall be secured without discrimination on any ground such as sex, race, colour, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, association with a national minority, property, birth or other status.” The list of grounds mentioned in article 14 and Protocol 12 is not exhaustive; therefore – despite not being explicitly mentioned- age discrimination is covered by these provisions. Unfortunately, only 8 out of the 28 EU Member States have accepted Protocol 12. As a result, the principle of equality on the basis of (old) age cannot be equally guaranteed across the European Union.

European Court of Human Rights

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) is based in Strasbourg, France and was founded in 1959. Today it is made up of 47 elected independent judges – one for each member country of the Council of Europe. The Court has the mandate to ensure that States comply with the European Convention on Human Rights. To do so, it rules on cases that are brought by individuals or governments. Individuals can bring complaints only once all possibilities of appeal have been exhausted in the member state concerned.

The Committee of Ministers helps to supervise how governments apply the Court’s decisions, but ultimately the extent and speed of implementation is left to national authorities. However, through its rulings the Court has led to the change of law in several countries and allowed victims whose rights have been violated to have access to effective remedies, including financial compensation.

For example, thanks to landmark decisions of the ECtHR 3:

- in Cyprus, an individual was able to vote

- in the Czech Republic, an older person was awarded a retirement pension that had been suspended

- Greece improved detention conditions for foreigners awaiting deportation

- Ireland decriminalised homosexual acts

- Latvia abolished discriminatory language tests for election candidates

- the Netherlands amended its legislation on the detention of patients with mental illnesses

Understanding the European Court of Human Rights

Make sure not to confuse the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) with other regional and international judicial authorities. For example, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) is based in Luxembourg and ensures compliance with EU law and in particular with the treaties establishing the European Union. The International Court of Justice is a judicial organ of the United Nations, based in The Hague, which settles legal disputes between States and provides legal advice on matters of international law.

If you want to know more about how the ECtHRs works, its achievements and challenges and how you can bring a case, you can watch a short film (in English or French), read this publication: The ECHR in 50 questions or watch this video that tells you how to lodge a complaint with the Court. In addition, the CoE website includes country profiles and thematic factsheets about its jurisprudence. To find out more about the impact of the ECtHR you can have a look at this infosheet.

The building of the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.

How does the European Court of Human Rights protect older people?

The rights of older people and age discrimination are not directly referred to in the ECHR. However, this does not mean that the Convention offers no protections for older people. All the provisions equally apply to everyone regardless of age and older people can claim their rights under the ECHR before national and European Courts.

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has interpreted the Convention broadly. For example, it has explained that the right to property, which is enshrined in article 1 of Protocol No. 1 also protects payments made to contributory pension funds (case Azinas v. Cyprus). That does not mean that the Convention guarantees a right to an old-age pension; States have a wide margin of appreciation to decide how insurance funds are organised and when pension rights can be limited. The Convention does not grant a right to a pension of a particular level, neither does it call for the automatic adaptation of the pension based on indexation (Federspev v. Italy). However, delayed payments of pensions, which result in losing significant part of their value can be considered an infringement of the Convention (Solodyuk v. Russia). Moreover, reductions of pensions due to austerity are considered reasonable as long as such measures are justified by extraordinary circumstances, in particular those imposed by the acute financial crisis. National authorities however need to make sure that their reforms do not disproportionately affect pensioners, for example by leaving them without any substantial means (Koufaki and ADEDY v. Greece). Hence, a substantial reduction of the amount of the pension could be regarded as a breach of the right to property (Müller v. Austria).

The Convention also protects pensioners from being treated differently based on their sex or other factors. Therefore, reducing the amount of pension, just because the woman in question is married constitutes unjustified discrimination (Wessels-Bergervoet v. the Netherlands). Excluding certain categories of civil servants from state pensions is also considered discriminatory (Fábián v. Hungary)

Moreover, the Convention covers extensively older people in care situations, especially those in residential care. For example, the Court ruled that the life of an older resident with Alzheimer’s disease had been put at risk through the negligence of the nursing home staff and that the police had not undertaken all necessary measures to pursue the necessary criminal or disciplinary sanctions (Dodov v. Bulgaria).

To have a better overview of the cases that are brought to the European Court of Human Rights and how rights in old age are protected through caselaw you can refer to this document: Factsheet – Elderly people and the ECHR, produced by the Council of Europe. In addition, AGE Platform Europe has published a briefing note outlining the most relevant Articles of the ECHR for older people’s rights. This document lists the different rights, makes clear how they are protected by the ECHR and recommends how they can best be used. Alternatively, you can watch a short interview with an official of the CoE, referring to some ECtHR rulings on the rights of older people.

Overall - despite the broad interpretation of human rights by the Court- it would be advisable for older people’s organisations also to look into the European Social Charter, which is a useful instrument to challenge reforms that infringe older people’s rights. You can find more about this in the following section.

EU accession to the European Convention on Human Rights

European Union accession to the ECHR will be a historic step in global human rights and will change the institutional and procedural protections of human rights (though not their essential substance) for EU citizens in ways not yet fully articulated. Currently, EU Member States are bound by the ECHR but the EU is not. As a result, whereas EU countries have a responsibility not to go against the provisions of the ECHR - even when they implement EU law - the EU is not legally obligated to change its legislation if it breaches the rights of the CoE Convention. This prevents legal clarity and fails to guarantee consistency between the EU’s Court of Justice and the CoE’s European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). Most importantly, under the current system the judgements of the ECtHR have limited impact in cases where amendments of EU law or policy are necessary to avoid future violations.

The ECtHR and EU law

The European Court of Human Rights has issued a list of rulings dealing with EU law, which can be found in this factsheet. To find out about what the practical impact of EU’s accession to the ECHR will be, you can have a look at this list of frequently asked questions.

When the accession will be completed the EU will have to fully respect the ECHR and will fall under the control of the European Court of Human Rights, which will ensure that human rights are further protected in all EU actions and policies – domestic and external. This will improve citizens’ protection, strengthen the binding effect of CoE law and improve sharing of expertise and promotion of human rights by the two organisations.

The path to accession has been a long one, however. Talks on how to solidify this partnership have been taking place within the EU and CoE, both formally and informally, since the late 1970s. The EU’s Lisbon Treaty (Article 6 TEU) and the CoE’s Protocol 14 to the ECHR rejuvenated the discussion in 2009/2010, respectively, and made EU accession to the ECHR a legal obligation and political priority for both organisations. Despite EU accession now being a legal obligation, there still also remain some areas of contention which have at times slowed down the negotiation process – for example, periodic objections of the UK and French governments.

Issues delaying the accession process have also emerged from the EU itself. For instance, at the end of 2014 the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) published Opinion 2/13, which ruled that the 2013 draft agreement on the accession of the EU to the ECHR was incompatible with EU law. One of the CJEU’s major concerns was that EU law could be undermined by the fact that it would be treated the same as that of all other Contracting Parties (nation-states) of the ECHR, despite the specific and different characteristics of EU law. For more information see the EU Law Analysis Blog and the European Law Blog, both of which explain the issues in more detail.

Following the CJEU’s 2014 Opinion, the accession of the EU to the ECHR has become more difficult. To respond to some of the main concerns several solutions were suggested, such as amending the EU Treaties to better observe ECHR law, but no official answers have as yet been offered by either organisation. EU accession to the ECHR would certainly be an important step in international human rights, but the problems noted above may cause significant further delays and compromise the full and effective protection of EU citizens.

EUROPEAN SOCIAL CHARTER

The European Social Charter is considered as the ‘sister’ treaty to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). It complements the set of civil and political rights found in the ECHR with a wide range of economic, social and cultural rights – such as social protection, working conditions, housing, education and healthcare. This treaty pays particular attention to groups in vulnerable situations, including older people, children, people with disabilities and migrants. Just like the ECHR, the European Social Charter has been amended several times. As a result of these amendments, there are different versions of the Charter and the extent of States’ obligations depend on which of these texts each government has ratified.

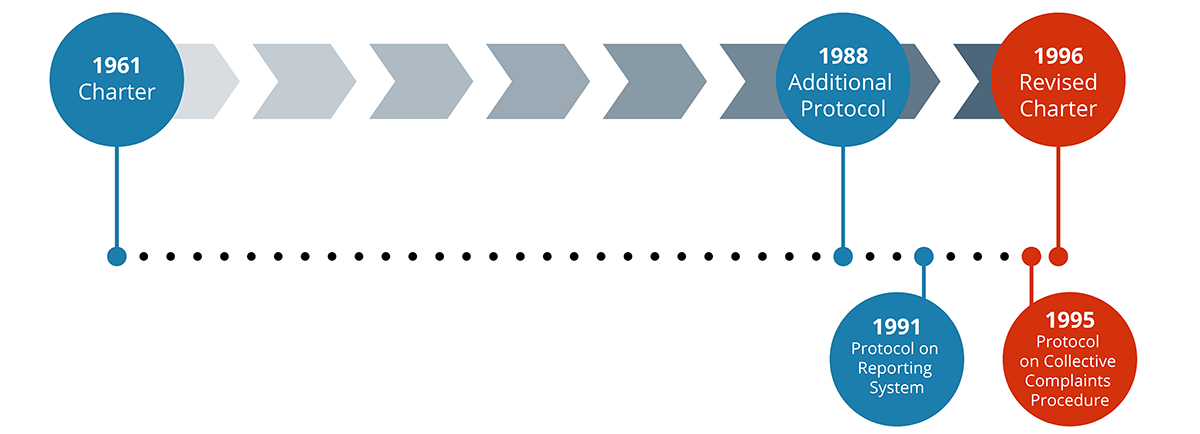

The original text of the European Social Charter was adopted in Turin in 1961 and aims to guarantee that governments’ policies respect, without discrimination, the rights included in its provisions. The treaty focuses on work-related rights, social and medical assistance, and the protection of the family, children, people with disabilities and migrant workers. In 1988 an additional protocol was drafted extending the set of rights covered by the European Social Charter, including:

- equal treatment of men and women in matters of employment and occupation;

- the right for workers to be informed and consulted;

- the right for workers to be involved in the improvement of their working conditions;

- the right for elderly persons to social protection.

The latter provision is very important since it includes the first ever legally binding agreement of states to protect and promote the rights of older people.

In 1996 a new version of the Charter was elaborated. This text, which is known as the Revised European Social Charter (RESC), brings together under a single instrument all rights guaranteed by the Charter of 1961, its additional Protocol of 1988 and furthers the protection of social rights, adding some new provisions and improvements in the text.

The Revised Charter of 1996 enshrined the rights to: protection against poverty and social exclusion; housing; protection in cases of termination of employment; and protection against harassment in the workplace. It improved protection of the rights of workers with family responsibilities and enhanced the rights of workers’ representatives. Additionally, it included a general principle of non-discrimination; strengthened gender equality in all fields covered by the treaty; enhanced protection of maternity and social protection of mothers; and increased the protection of employed children and handicapped people.

Moreover, two protocols address procedural aspects of the monitoring of the implementation of the Charter. The 1991 Protocol deals with the process of reporting and monitoring of the treaty and the role of respective CoE bodies. Due to a minority of States not having ratified it, officially this Protocol has never entered into force. In practice however, based on a decision taken by the Committee of Ministers, its provisions are already applied. The 1995 Protocol strengthened the enforcement of the European Social Charter allowing social partners and non-governmental organisations to lodge collective complaints about violations of the Charter by States. The European Committee of Social Rights examines these cases and decides whether the State in question complies with the treaty’s requirement. The mechanisms of reporting and complaint will be explained in more details in the following sections.

Timeline of the development of the system of the ESC. Image credit: CoE

European Parliament report on the implementation of the European Social Charter by the European Union

As it is a goal of the European Union to accede to the ECHR (see relevant section for more information), some argue that it may one day also be similarly important for the EU to accede to the European Social Charter – given that it is the counterpart to the ECHR. In January 2016, the European Parliament published a report suggesting four potential ways for the EU to be more involved in the implementation of the ESC, which could become more important in the future:

- The ESC could become a more explicit source of EU law;

- The ESC could be mainstreamed into the European Commission’s impact assessments prior to making a policy proposal;

- EU Member States could be encouraged to update their national legislation to better define a common approach towards the ESC within the EU;

- The process of accession of the EU to the ESC could be formally initiated.

While undoubtedly the EU’s accession to the European Social Charter (or any of its revised versions) would be an important step for the rights of older persons, and for the protection of social rights in general, there may be some challenges to face before this happens. The aforementioned report, for example, concludes that “the status of the European Social Charter in the law- and policy-making of the EU remains deeply unsatisfactory, and the risk of tensions will increase in the future.” Moreover, in their answer to a Parliamentary question, the European Commission – while acknowledging the convergence between the European Social Charter and EU law – they clarify that ‘[t]he Council has not discussed the issue of a possible EU accession to the European Social Charter’.

The European Social Charter is one of the most widely acknowledged human rights treaties, with 43 of the 47 Council of Europe member countries being party to either the 1961 or the 1996 charter (including every EU Member State). Moreover, many of the provisions included in the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights replicate the rights included in the European Social Charter.

European Social Charter provisions on the rights of older people

Although older people were not explicitly mentioned in the European Social Charter of 1961 thanks to the 1988 Protocol an article on the rights of the elderly to social protections was added. This provision was integrated in the Revised European Social Charter (RESC) of 1996. As a result, countries which have ratified either the RESC or the additional protocol – unless they have made a reservation about this provision - are bound to respect the rights of older people. While your country may not have signed up to the 1998 Additional Protocol, to Article 23 of the 1996 RESC, or indeed signed up to the RESC at all, there are still human rights protections in place for older people in Europe which can be relied upon, as some of the most important provisions for older persons are already covered by the 1961 Charter. This includes provisions referring to social protection, medical assistance and the independence of disabled people, such as the right “to provide or promote appropriate vocational guidance, training and rehabilitation” (Article 1 – the right to work), and the governmental obligation “to raise progressively the system of social security to a higher level” (Article 12 – the right to social security).

1961

1988

1996

European Social Charter (ESC)

Additional Protocol to the 1961 European Social Charter (AP)

Revised European Social Charter (RESC)

Older people are not directly mentioned in this treaty (although they are de facto covered by phrasing like “everyone shall […]” in many relevant provisions).

A new provision was introduced specifically for older people:

“Article 4 – Right of elderly persons to social protection”

Older people continue to be protected by the same wording as in the AP:

“Article 23 – The right of elderly persons to social protection”

“With a view to ensuring the effective exercise of the right of elderly persons to social protection, the Parties undertake to adopt or encourage, either directly or in co-operation with public or private organisations, appropriate measures designed in particular:

-

to enable elderly persons to remain full members of society for as long as possible, by means of:

- adequate resources enabling them to lead a decent life and play an active part in public, social and cultural life;

- provision of information about services and facilities available for elderly persons and their opportunities to make use of them;

-

to enable elderly persons to choose their life-style freely and to lead independent lives in their familiar surroundings for as long as they wish and are able, by means of:

- provision of housing suited to their needs and their state of health or of adequate support for adapting their housing;

- the health care and the services necessitated by their state;

- to guarantee elderly persons living in institutions appropriate support, while respecting their privacy, and participation in decisions concerning living conditions in the institution.”

How can you find out which ESC provisions your country is bound by?

Because of divergences between these three treaties, not all countries are bound by the same standards. To understand which provisions apply to your country, you need to know if your country is party to the 1961 or the 1996 Charter and whether it has ratified the additional protocol. Moreover, governments may decide not to accept certain provisions; hence, specific rights may not be applicable in your country. Nevertheless, all States are obliged to accept a minimum of core articles of the Charter. It is particularly important to be aware of the safeguards that apply in your country to ensure that your policy and advocacy work is based on the international commitments that your government has made in the frame of the system of the ESC.

The following table gives an overview of the States’ obligations under the European Social Charter 4. Remember that a country is not bound by a treaty unless it ratifies it; a signature is not sufficient to create legal obligations to Member States. The majority of EU countries have ratified the 1996 Revised Charter. However, 8 Member States have not done so and are only bound by the 1961 ESC. These cases are highlighted with notes in parentheses. Among these, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark and Spain have also ratified the 1988 Protocol, which also includes an article on the rights of older people. The numbers in the parentheses indicate that those countries, which are not bound by the RESC, have ratified the 1961 Charter and – where it applies – also the 1988 protocol. Where no date is mentioned in the third column, that country has ratified the 1996 RESC. The fourth column shows which countries accept collective complaints by international NGOs and social partners. Only Finland has accepted the submission of collective complaints also by national NGOs (fifth column). Finally, the last column clarifies whether the provision on the rights of the elderly applies to your country. Depending on which version of the Charter your government has ratified this may refer to Article 4 of the 1988 Protocol or Article 23 of the 1996 Revised Charter. Nevertheless, the content of these two articles is identical and therefore it makes no difference where your government’s obligations derive from. Unfortunately only half of EU’s Member States have accepted the provision on the rights of the elderly. Despite this, you may refer to other rights of the European Social Charter to claim the rights of older people, such as the general right to social security, among many others.

To have more details about which provisions of the European Social Charter have been accepted by which EU countries please follow this link. For more up to date country-by-country information, you can also refer to the relevant CoE webpage. To find out how the national law of each Member State conforms to individual Social Charter provisions please follow this link.

(8 bound by 1961 Charter,

4 of which also bound by 1988 Protocol)

Turin Process

In October 2014, at a high level conference on the European Social Charter (ESC), the Turin process was launched and remains ongoing. The aim of the Turin Process is to highlight the efforts that continue to be made to shine a light on economic, social and cultural rights in a European context – particularly in an era of austerity which threatens to undermine many aspects of the European project, including older people’s rights.

The initial conference brought together European policy-makers to reaffirm the importance of social rights, with particular attention paid to the effects of austerity measures and the national implementation of human rights. The aim of the Turin process as a whole is to improve the implementation of social rights in Europe by ensuring they continue to be given the appropriate attention.

European Committee of Social Rights

The European Committee of Social Rights (ECSR) is the monitoring body for the European Social Charter. Unlike the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), it is non-judicial and so cannot pass directly binding judgements, although it can clarify the law and provide a basis for positive legal developments on a national level. The Committee is comprised of 15 members elected by the CoE Committee of Ministers. They have a 6-year mandate, which can be renewed for one more term.

The European Committee of Social Rights monitors States’ compliance with the Charter using two complementary mechanisms. Firstly, it decides on collective complaints lodged by social partners and non-governmental organisations. Secondly, the Committee examines national reports through a process known as ‘Reporting System’. The following sections explain these procedures in details.

Monitoring how your country implements the European Social Charter

The Department of the European Social Charter of the CoE publishes regular updates on how each Member State applies the treaty. Country factsheets explain which provisions apply to each country and also highlight the most important complaints as well as the Committee’s conclusions and recommendations. To access this information, which will be very useful for your organisation to monitor whether your country complies with its obligations under the Charter, you can visit this webpage. The European Committee on Social Rights also publishes an annual report, which gives an overview of their activities and they publish their conclusions and decisions on collective complaints in an online database called HUDOC. Using this system you can select the country you are interested in and have access to all the relevant information. You can further narrow your research based on the type of document you are looking for, the period of focus or the article of the Charter you are interested in. If you want to have more detailed information about your government’s progress in implementation the CoE treaties, you can also refer to the annual reports they submit to the ECSR under the Reporting System, where they explain what they have done to comply with the Charter’s provisions.

The mechanism of Collective Complaints

The Collective Complaints procedure was introduced through the 1995 Protocol to increase the speed, effectiveness and impact of the implementation of the Charter by allowing NGOs and social partners to bring cases about violations of the European Social Charter to the attention of the European Committee of Social Rights. As its name suggests, the only complaints that can be submitted must relate to collective and systematic violation of human rights, rather than to individual breaches. This will most often consist of laws or policies which create disadvantages for certain groups.

For example, collective complaints could be based on evidence that a certain policy excludes older people, due to age limits; argue that the lack of national legislation prohibiting age discrimination creates specific disadvantages for older people that amount to breaches of their right to remain integrated in their community; or describe concrete ways in which austerity measures have disproportionately affected pensioners, by creating poverty gaps.

Organisations must meet certain criteria and apply in order to be able to use the Collective Complaints procedure. The EU’s European social partners, such as the European Trade Union Confederation and Business Europe, are entitled to lodge complaints, as well as national employers’ organisations and trade unions. Additionally, international NGOs which hold participatory status with the Council of Europe (see last section for more information) also have the same right. Finally, any state may grant certain national NGOs the ability to lodge complaints, although to date only Finland has made use of this possibility.

Collective complaints do not address individual situations and they do not require that the organisation making the complaint is a victim of the violation. Therefore, unlike cases brought to the European Court of Human Rights, it is not necessary to seize a national court before contacting the European Committee for Social Rights.

How to submit Collective Complaints

In order to submit a collective complaint first you need to make sure that your country has accepted this procedure, by ratifying the 1995 Protocol. Then you need to gather evidence about the failure of your government to comply with one or more of the Charter’s provisions that they are bound by. To verify, whether your country allows the submission of collective complaints and what is the extent of their obligations, you may refer to the table included in Case Study 11, which provides practical information.

Remember that as a national NGO – with the exception of organisations from Finland – you are not allowed to lodge a complaint. However, AGE Platform Europe – as an international NGO (INGO) has applied and been granted the ability to submit complaints of violations of the European Social Charter using the Collective Complaints procedure. Hence, AGE can collaborate with its national members to prepare collective complaints aiming to achieve positive change. We can also rely on our network of prominent legal experts to help with this process.

As of October 2016, NGOs from the following countries, which have accepted this procedure, can submit complaints through AGE: Belgium; Bulgaria; Croatia; Cyprus; Czech Republic; Finland; France; Greece; Ireland; Italy; the Netherlands; Portugal; Slovenia; Sweden.

If the complaint complies with the formal criteria of admissibility, then the Committee rules on the substance of the case. To do so it invites both the claimant organisation and the State concerned to submit their views in writing. The Committee may also decide to hold a hearing where both sides will present their arguments.

Once the European Committee of Social Rights (ECSR) decides whether or not there has been a violation of the Charter, it shares its conclusions in the form of a report with the Committee of Ministers as well as with the State and organisation concerned. On exceptional cases and in order to avoid any serious violations of rights, the ECSR may also suggest immediate measures that need to be taken by the government after or in advance of the Committee’s decision.

The Committee’s decisions do not have the same legal force as a court’s rulings; although they are not directly enforceable, national authorities need to take the necessary measures to give them effect. The role of the Committee of Ministers is crucial in order for the ECSR deliberations to become operational.

If the ECSR declares a violation of the Charter, the State concerned should notify the Committee of Ministers about action they plan to take to rectify the situation. The Committee of Ministers, which is made up of representatives of all CoE countries, can adopt a resolution or a recommendation addressed to the government outlining necessary steps so that the rights under the European Social Charter do not remain theoretical but are given full effect.

States are also required to report on their efforts to reform their policies and laws in order to comply with the Committee’s conclusions, using the Reporting System described below.

What is the impact of Collective Complaints at grassroots level?

Collective Complaints have the potential to play a significant role in inciting legal and/or policy changes on a national level. One such case was brought before the European Committee of Social Rights in 2011 by the Central Association of Carers in Finland, who exercised the right given to them by the Finnish government to lodge such complaints.

The Central Association of Carers in Finland alleged that older people’s rights were violated by Finnish legislation that denied equal access to informal care allowances or alternative support for older people in Finland who required long-term care. They supported that State provisions were applied very differently in the 336 Finnish municipalities, leading to large inequalities across the country.

On the basis of Article 23 of the Revised European Social Charter (the right of elderly persons to social protection), the ECSR decided that the Finnish government had indeed violated the Charter since the national legislation excluded a part of the older population from access to informal care allowances or other alternative support.

Following the ECSR’s decision, the Finnish government has made progress to resolve this issue by introducing new legislation to better protect older people requiring long-term care, such as the Act on Services for Older Persons (2013) and the Act on the Arrangement of Social Welfare and Health Care Services (2015). It has also set strategic goals and action plans, alongside providing more funding to local support services providing informal care. While Finland’s progress is positive, it remains ongoing and in a 2014 assessment it was noted that “the situation has not been brought into conformity with the Charter”. Another assessment is due to take place in October 2017, at which time it is likely that there will have been further improvements.

As this case demonstrates, the Collective Complaints procedure can have a crucial impact on national law, policy and practices, and ultimately also on the lives of older people whose rights have been violated. It is important that AGE Platform Europe members communicate all examples of problematic practices in national law and/or policies to the AGE Secretariat so that we can help to eliminate the many structural barriers still existing in Europe which prevent older people from enjoying their rights.

The Reporting System

The ECSR is also responsible for a supervisory system that requires member countries to submit annual reports about how they have implemented the different provisions of the European Social Charter. States’ reporting obligations derive from the 1961 Charter and the 1991 Protocol, which is applied in practice thanks to a decision by the Committee of Ministers. These national reports can be very useful for NGOs because they outline country-specific situations in one thematic area of rights, such as “health, social security and social protection”. After submission, the Committee provides conclusions and recommendations on the reports, which can also be used to hold national governments to account. You can refer to all State Reports and Committee Conclusions using the linked European Social Charter Database (HUDOC).

More concretely, according to this procedure every year national governments do not have to report on the full range of rights protected by the European Social Charter treaties. Instead, they have to provide information on a rolling basis for one of the following 4 groups of provisions: Employment, training and equal opportunities; Health, social security and social protection; Labour Rights; and Children, families and migrants. Article 23 on the rights of the elderly falls under the second group. As a result, each article of the Charter and its implementation through national law and measures are examined every 4 years. To further alleviate the workload of States that have accepted the mechanism of Collective Complaints, the concerned governments follow a simplified system of reporting, which is described in details in the webpage of the CoE.

Accessing the calendar for the Reporting System

It is useful to know when your country is supposed to submit its annual report and when the Committee is expected to deliver its conclusions so that you can comment and follow up on their findings. To access this information you can look into the timetable provided by the Committee. For example the deadline for the submission of State reports on the implementation of article 23 on the rights of the elderly ended on 31st October 2016, whereas the ECSR will adopt their conclusions about States’ compliance with this provision in December 2017, after having reviewed all country-specific information.

After reviewing the national reports, if the European Committee of Social Rights concludes that a State’s laws and policies are not in conformity with the Charter, they refer their observations to the Governmental Committee. The Governmental Committee is comprised of representatives of States but also involves European and international employers’ organisations and trade unions. They are responsible for assessing whether the planned national reforms and progress to remedy the violation are satisfactory. If a government fails to set out the measures that they plan to take to improve their law and practice, the Governmental Committee can suggest to the Committee of Ministers to prepare a Recommendation calling on the State concerned to take all the necessary action in order to comply with the Charter and the Committee’s conclusion.

What is the added value of the Reporting System?

The European Committee of Social Rights (ECSR) in 2015 published a comment on an annual report submitted by Bulgaria with relation to individuals’ right to benefit from social services. The ECSR had concluded that it had not been established in the report that the number of social services staff was adequate to users’ needs. Following this initial conclusion, Bulgaria had been required to produce an additional report addressing the omissions and providing the missing information.

Following receipt of this additional report, however, the ECSR again concluded that more information was needed to ensure that Bulgaria was providing a sufficient level of social services and they requested a further report containing the necessary information. To ensure full compliance, the Committee was very specific in its request for information: “The Committee requests clarification as to the distribution of staff between the state and the municipal level and it asks that the next report contain estimates (or examples) of the number of staff involved in social services provision as part of municipal activity and with private providers.” The conclusion of this case remains pending as the information requested has not yet been provided by the Bulgarian government.

This example demonstrates what kind of impact the Reporting System can have. In this case, Bulgaria did not submit enough information to show that individuals living in the country had sufficient access to social care. The Committee is able to put pressure on governments to provide information, which ensures transparency and accountability about the state of protection of rights within their territory. Reading the national reports and the ESCR’s conclusions NGOs are in a position to call for additional measures in case the government fails to rectify the situation. Based on country information they may also decide to lodge a collective complaint, which is another way to put more pressure to the government in order to make positive reforms.

3.4 Other CoE bodies and instruments on human rights

In addition to the main human rights treaties, the Council of Europe (CoE) has introduced an extensive framework to protect and promote human rights, composed of monitoring mechanisms, policymaking bodies, soft instruments, awareness-raising projects, but also binding legal texts in a number of areas.

The CoE Secretariat includes a division on Human Rights Law and Policy, which is in charge of carrying out the organisation’s work in this area. Based on the priorities decided by the CoE governing and decision-making bodies, this unit prepares binding and non-binding instruments on human rights; assists the Secretary General and the Steering Committee on Human Rights (CDDH) in their work; and ensures links with the activities of the European Union and the United Nations. The Human Rights division is also responsible for supporting the negotiations for EU’s accession to the ECHR.

The Steering Committee on Human Rights

The Steering Committee for Human Rights (CDDH) is composed of representatives of the 47 member states of the Council of Europe. Its role is to set up commonly accepted standards with the aim of developing and promoting human rights in Europe and improving the effectiveness of existing CoE instruments, in particular the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The work of the CDDH is overseen by the Committee of Ministers and meets regularly to discuss a variety of topics. Other CoE bodies, the European Union, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and some international NGOs can also participate in their meetings.

The Steering Committee for Human Rights can moreover create smaller sub-committees to work on specific priority areas. For example, in 2012 the CDDH decided to set up a group of experts, known as CDDH-AGE, to elaborate a non-binding instrument on the promotion of the human rights of older persons. More information about this initiative and AGE’s role in it can be found in Case Study 15.

The Committee of Ministers and the Parliamentary Assembly (PACE) are the Council of Europe’s two main decision-making bodies. The Committee of Ministers is the representative body of national governments, while PACE is the voice of the 800 million people living in Council of Europe member countries. The Congress of Local and Regional Authorities represents regional or municipal authorities.

How to engage with the Committee of Ministers, PACE and the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities

Everything produced by all three institutions is adopted by consensus and so can be used for advocacy and awareness-raising in all Council of Europe member countries. Consequently, one very important action is to communicate information about the work of these institutions (explained in more detail below) to your network and to older people in your country or locality. To effectively advocate for positive change for older people, it is necessary to raise awareness of the different tools that already exist.

All three of these bodies are active in many areas relevant to older persons. Although their work is mainly aimed at providing policy guidance and is not directly enforceable, their actions can be used to hold national governments to account, ensure older people’s rights remain high on political agendas, and are sometimes the first step towards introducing binding legislation. The consistent use of human rights language and approaches in the actions of these bodies also helps to encourage national governments, who have not already done so, to integrate human rights in future legislation.

Congress of Local and Regional Authorities

As many areas of policy relevant to older people – such as long term care and urban development – are the responsibility of local or regional authorities, adopted texts of the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities are frequently pertinent. To search for relevant texts you can use this database.

In 2007, for instance, the Congress adopted two texts concerning intergenerational cooperation and participatory democracy (Recommendation 209 and Resolution 228). Both aim to highlight the growing gap between younger and older people that undermines social cohesion in localities across Europe, and both include a draft Manifesto on Intergenerational Cooperation and Participatory Democracy, intended for use by local or regional authorities as a guiding framework to improving intergenerational solutions to age-related problems.

In the Manifesto it is suggested that local, regional, national and international intergenerational projects should be given particular support, and that bodies should be created (‘intergenerational centres’) in all localities to facilitate learning, training, communication and ultimately the increased social inclusion of both younger and older persons. Another suggestion is that voluntary public services be established (if they do not already exist), for the particular benefit of older people in need of social care, or simply a wider local network.

Secretary General

Thorbjørn Jagland, Secretary General of the Council of Europe since 2009

The Secretary General of the Council of Europe is the organisation’s most senior official and is responsible for its strategic management. Among other things, the Secretary General can request explanations from member countries about how a right (such as non-discrimination) is protected by domestic law – although, exactly how, when and on what subject to do so is left to their own discretion.

Secretary General’s Annual Report

The Secretary General publishes every year an Annual Report, detailing their perspectives on what should be important areas of focus for the organisation. Thorbjørn Jagland highlighted some areas relevant to the protection of older people’s rights in his 2015 report:

- Quality of anti-discrimination measures: Gaps and loopholes in, or omissions of, anti-discrimination legislation still exist across Europe, especially in specific areas like employment discrimination on the grounds of age or disability.

- Effective social rights enforcement: “Specific rights for the elderly and for people with disabilities constitute essential factors of social inclusion”.

Commissioner for Human Rights

Nils Muižnieks, Commissioner for Human Rights at the Council of Europe since 2012

The office of the Commissioner for Human Rights was established in 1999 with the non-judicial but broad purpose of promoting education in and awareness of human rights in Europe. The Commissioner is the chief human rights official at the Council of Europe as their analyses and actions can go further than the Secretary General in this area – including by making regular country visits. The Commissioner has a mandate to provide advice and information, as well as to put pressure on governments by increasing the visibility of human rights issues.

Since his election in January 2012, the Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights has been Latvian national Nils Muižnieks. He has published extensively on human rights issues, and has specialised in discrimination and minority rights throughout his career. Hear Muižnieks introduce himself and his work here (video in English with French subtitles).

The Commissioner makes country visits where he meets with government representatives, the judiciary, everyday human rights activists and individuals. Afterwards, the Commissioner publishes a report or letter containing a full assessment of the human rights situation in that country, including recommendations.

The Commissioner’s various publications can be used to support human rights advocacy in CoE member countries because they provide detailed information about the situations of individual countries by exploring trends and providing recommendations for improvement.

Older people in the work of the Commissioner for Human Rights

In a 2012 country report about Austria, the Commissioner for Human Rights dedicated one whole section of the document to the human rights of older people. This focus is not unusual (although not mandatory) given the common demographic changes being experienced across Europe.

In his report, the Commissioner praised Austria’s Federal Senior Citizens Advisory Council, a forum where representatives of senior citizens’ organisations can participate in relevant policy discussions. He also noted that relevant analyses are regularly commissioned by the Austrian government – including one about ‘Gender Mainstreaming in Senior Citizens Policy’ – demonstrating a political understanding of older people’s rights and a willingness to explore different policy solutions.

Importantly, the Commissioner also identified some issues for improvement. Firstly, the problem of violence against older persons – particularly that carried out by people within their family or neighbourhood, or within homes or institutions. Secondly, age discrimination in the labour market. In his closing comments, the Commissioner made recommendations which could be used to hold the Austrian government to account for non-action if necessary.

In his conclusions, the Commissioner recommended:

- Adapting social protection, healthcare and housing policies to improve older people’s access and participation;

- Ensuring adequate numbers of skilled staff to provide care services for older people;

- Improving monitoring in care institutions through regular inspections;

- Making necessary reforms to efficiently protect older people against violence;

- Strengthening safeguards to protect those living alone and in isolated areas.

Follow the Commissioner’s work in your country

All of the Commissioner’s work is brought together into a yearly ‘Activity Report’. This document can be used as a guide to the different publications and actions of the Commissioner because it provides an overview of all advices given, countries visited and reports published. To find out more about the human rights situation in your country, as reported on by the Commissioner for Human Rights, you can also follow this link, which includes country-by-country information.

Committee of Ministers

The Committee of Ministers is made up of the national Ministers of Foreign Affairs of all 47 Council of Europe member countries and their Deputies. It can prepare and adopt Conventions, Agreements, Declarations, Resolutions and Recommendations, some of which are particularly relevant to older people’s issues.

Some important texts adopted by the Committee of Ministers with direct relevance to older persons are included in the below table. This list is not exhaustive; to search for other relevant documents you can use the following link.

Recommendation on the promotion of the human rights of older persons

In 2014 the Committee of Ministers adopted a Recommendation on the promotion of the human rights of older persons. Although non-binding, this is a significant measure because it is the first European human rights instrument that specifically targets older persons.

The Recommendation emphasises that the rights of older people are still too often ignored or denied in Europe as a result of prevailing stereotypes; consequently, it affirms the human rights of older persons and measures that can be taken to prevent discrimination. The document also explicitly highlights that all human rights and fundamental freedoms enshrined in existing instruments apply to older persons on an equal basis with other groups.

A broad cross-section of challenges facing older persons is covered in the Recommendation: non-discrimination, autonomy and participation, protection from violence and abuse, social protection and employment, care, and the administration of justice. Inspired by the EU-funded EUSTaCEA Project, which was coordinated by AGE, the Recommendation includes a list of national good practices that can be used as a compass for positive policy change. Importantly, the CoE’s Recommendation encapsulates an even wider set of rights and good practices than those covered by the project, which focused on aspects of long-term care.

To prepare for this Recommendation, an expert Working Group (CDDH-AGE) was tasked with exploring options for its development. AGE Platform Europe participated in these meetings providing comments and written recommendations that suggested potential improvements to the Recommendation. AGE played an important role in shaping the final text in some specific ways:

- Bringing a pragmatic approach to the whole process based on the views of older persons

- Searching for a holistic approach to the rights of older persons

- Including a reference to social and economic rights

- Ensuring that financial abuse is included as a form of abuse

- Improving the parts of the text related to autonomy and care, stressing in particular the importance of care at home and the role of informal carers

- Introducing a provision stating that older people should be consulted prior to the adoption of measures that have an impact on the enjoyment of their human rights

- Building on the outcomes of two influential projects in the field of long-term care, namely the EUSTaCEA and WeDo projects coordinated by AGE, and including them in the list of good practices and explanatory report.

This Recommendation has great potential to impact work on the ground if it is taken into account in national policymaking. It proposes concrete ways and practices which make it appropriate to be used as a ‘soft’ reference document for older persons’ advocacy. Additionally, all Council of Europe member countries have been invited to produce a one-off report on the implementation of the Recommendation five years after it being adopted (i.e. in 2019), so it is something that can also continue to be formally pursued at a national level.

You can translate and share the Recommendation to ensure it plays a suitably key role in holding governments to account. It is currently available in English, French, Dutch and Polish, but work still needs to be done to ensure it is translated into other languages. As the Recommendation is due to be assessed in 2019, you can also contribute to its distribution and improvement by gathering information about how far it has been taken into account by your government since its adoption by the Committee of Ministers.

Parliamentary Assembly

The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) consists of 324 principal members and 324 substitute members from all 47 CoE countries. Unlike the EU’s European Parliament, in which members are directly elected on a European level, the CoE’s Parliamentary Assembly is made up of elected officials of national parliaments. The objective of the Assembly is to provide a forum in which states can discuss (among other things) human rights issues and hold governments to account through non-binding measures.

How the Parliamentary Assembly (PACE) works

If you would like to read more about how the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe operates, you can refer to this useful document, prepared by the different bodies making up PACE. The document is directed at internal staff, rather than at external stakeholders, but it nevertheless offers a clear overview of the inner-workings of the Parliamentary Assembly.

The Assembly and its Parliamentary Committees can advise, demand action, monitor progress, question Heads of State or Government, observe elections or recommend specific sanctions. Texts they adopt include ‘Resolutions’, ‘Recommendations’, and ‘Opinions’. Despite their conclusions not being legally binding, the fact that the Assembly represents over 800 million European citizens gives their actions the sufficient authority to hold governments to account for violating agreed principles.

How to contribute to the work of the Parliamentary Assembly

The PACE sometimes works on thematic reports, and may even organise fact-finding visits in some countries in order to evaluate the situation on the ground. For example, one of these initiatives focuses on the rights of older people and their comprehensive care. On this occasion, the Rapporteur of PACE, Lord Foulkes, has held consultations with NGOs and other stakeholders (in particular the World Health Organisation) and visited Denmark and Romania where he met with representatives of organisations of older people, patients and carers, among others. Being informed about the activities of the CoE gives you the opportunity to contribute to such initiatives and ensure that their findings are informed by the experiences and views of older people in your country.

The PACE has also adopted many texts directly relevant to older persons, which can be found in the table below. This list is not exhaustive; to search for additional PACE adopted texts you can use this database.

2007 PACE reports on the human rights of older persons and their comprehensive care

The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) has adopted in June 2017two texts spelling out a series of steps that are needed to protect the rights of older persons.

In a resolution adopted unanimously, based on a report by Lord Foulkes from the United Kingdom, the PACE recognizes that older people suffer from widespread negative stereotypes, which are at the root of age discrimination and elder violence, as well as of their isolation and exclusion. Among the actions proposed, the Assembly called on EU Member States to ensure a minimum living income and appropriate housing to enable older persons to live in dignity. They should also prohibit by law age discrimination in the provision of goods and services and undertake a series of measures in the health and social care sector. These include the suggestion to adopt a charter of rights for older persons in care settings, which could be used to empower older persons, as well as to monitor long-term care by an independent body.

In its recommendation the PACE also notes initiatives by other regional organisations to enshrine the rights of older persons in legally binding instruments and calls on the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe to consider the necessity and feasibility of drawing up a legally binding instrument in this field.

These documents provide another ground to pay attention to the situation of older persons and to think about concrete measures that can strengthen the protection of their human rights. But in order for these recommendations to be effective civil society needs to be active in pushing for the adoption of the proposed measures at national level and also for further debate regarding a new legally binding instrument.

You may have access to the report, resolution and recommendation of the PACE here

Capacity building

One of the most important tasks undertaken by the CoE in the field of human rights is awareness-raising and exchange of good practices. The CoE runs training programmes that aim to build the capacity of legal professionals, public officials and civil society to use the European Convention on Human Rights and the European Social Charter, offering practical guidance in order to fulfil rights and avoid breaches. Such activities ensure the effective implementation of CoE legal standards at national level. These projects are often co-funded by the CoE and the EU; they may focus on a single country or a thematic area, such as fighting racism or ensuring privacy. More information about some of these activities is available through the Human Rights National Implementation Division.

The HELP programme on human rights education

The ‘Human Rights Education for Legal Professionals’ (HELP) programme is targeting judges, lawyers and prosecutors. It includes a pan-European network, which develops national trainings and exchanges experience and material in human rights education; an online self-learning platform; and an adapted training methodology for legal experts. HELP supports legal professionals from CoE countries to deepen their knowledge and skills on how to use the ECHR and the European Social Charter in their daily work. For practitioners from EU countries, a dedicated programme called HELP in the 28 was developed and funded by the EU.

Equality and Social Cohesion

The CoE pays particular attention to the rights of groups in vulnerable situations, such as children, minorities, Roma, LGBT, and people with disabilities, but also to transversal issues, including gender equality, racism and migration. This is reflected in the organisation's work priorities, but also its secretariat structure, which includes specialised divisions and expert committees. Some areas are more developed than others: for example, the Gender Equality Commission (GEC) is a group of experts appointed by Member States, with a mandate to support CoE bodies in order to effectively mainstream gender equality and improve the protection of women’s rights. Likewise, there is a Committee of Experts on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which – among others – is involved in the implementation of the CoE Disability Action Plan, soon to be replaced by a new Disability Strategy.

European Social Cohesion Platform

Until the end of 2015 the European Committee for Social Cohesion, Human Dignity and Equality (CDDECS) had a task to oversee and coordinate the intergovernmental work of the Council of Europe in the fields of social cohesion, human dignity, equality and anti-discrimination, and to advise the Committee of Ministers on all questions within these areas. The Committee also supervised the expert bodies on gender equality, the rights of the child and people with disabilities. Although CDDECS was discontinued, the European Social Cohesion Platform was launched for the period 2016-2017 with a similar mandate, focusing in particular on the protection of migrants and refugees; the impact of the crisis on social rights; vulnerable groups; non-discrimination and gender equality.

The CoE also promotes enhanced cooperation between governments on youth policies. They fund programmes and activities at local, national and European levels but also develop legal instruments to promote the participation and education of young people. They organise regular meetings with representatives of youth organisations, ensuring that their views guide CoE work. Last, the CoE supports financially NGOs and relevant initiatives.

Although there is no specific body or strategic priority dealing with older people, their rights are taken into account by various CoE bodies and instruments. The following sections explain some of the most relevant provisions for older people within the CoE framework.

Mainstreaming older people’s rights across all CoE processes

It is important that national NGOs raise awareness of the challenges faced by older people so that their governments take these into account when they work with the various CoE bodies. For example, even though older people are not directly mentioned in the CoE Disability Action Plan, this is an area particularly relevant older people who need care and assistance as they get older. Getting to know how the CoE works will allow you to build bridges between your work at national level and what your government promotes within the CoE processes. You should regularly remind your country’s representatives to take into account older people in the activities of all the committees and bodies of the CoE. For example, seizing the opportunity of the revision of the Council of Europe Disability Strategy AGE argued that the future roadmap for action in this area should include explicit reference to age discrimination. We also recommended taking action to improve awareness of the relevance of disability for older people and ensure that representatives of older people are involved and consulted by national and European bodies.

Health and Biomedicine

The protection of health counts among the CoE’s core objectives. For example, the European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines and Healthcare promotes and monitors the application of standards for medicines and their safe use.

Training Programme ‘Health Literacy for Elderly People’

A project entitled "Citizens' consultation platform on the right to the protection of health" aimed to empower citizens and increase their participation and consultation in health-related processes, through improved health literacy and education. In the frame of this programme a training course for older persons was developed. This helps older citizens prevent and manage their illness, take informed decisions and improve their overall health and well-being.

The CoE is also at the forefront of establishing the fundamental principles applicable to health care, medical research, biotechnology and genetic testing. In April 1997 the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine (informally the Oviedo Convention) was opened for signature. This is relevant for the rights of older people because it remains the only legally binding international instrument, which aims to protect citizens and avoid abuses linked with scientific progress in the fields of biology and medicine. The Convention establishes important principles related to the primacy of the human being (Article 2), equitable access to healthcare (Article 3), consent and the protection of persons not able to consent (Articles 5 and 6) and respect of previously expressed wishes (Article 9).

The principles of the Oviedo Convention are further developed in 4 additional protocols: on the Prohibition of Cloning Human Beings; on Transplantation of Organs and Tissues of Human Origin; on Biomedical Research and on Genetic Testing for Health Purposes. In addition, the Committee on Bioethics has adopted a number of Recommendations and elaborated several reports that enhance understanding and provide guidance for health professionals and researchers.

Ensuring patients’ rights in end of life

In 2014 the Committee on Bioethics (DH‑BIO) of the Council of Europe drafted a ‘Guide on the decision-making process regarding medical treatment in end-of-life situations’. This is a useful tool for older people who sometimes have to face difficult decisions with regard to medical treatment in end-of-life situations. Based on the principles of the Oviedo Convention, it provides guidance for health professionals, patients, their carers and families and is available in several European languages.